Hogarth Gallery1- Beggar’s Opera III, x

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Beggar’s Opera III, xi

1729

Oil on canvas

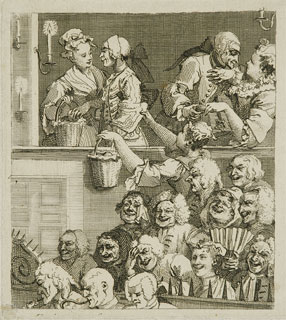

Hogarth’s painting depicts the psychological and comic climax of The Beggar’s Opera, set in Newgate Prison. Macheath, a gentlemanly highwayman, stands in chains at center stage. His two wives, Polly Peachum and Lucy Lockit, make appeals to their fathers, informant, and jailer respectively, to perjure themselves in support of Macheath. Polly sings:

When my hero in court appears,

And stands arraigned for his life,

Then think of poor Polly’s tears;

For ah! Poor Polly’s his wife.

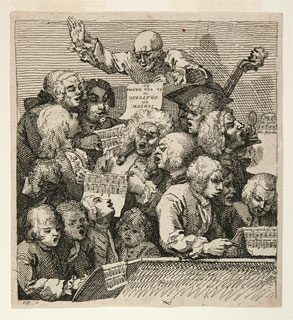

Part of the humor derives from the necessity for Macheath to choose between his wives; he has just sung, “Which way shall I turn me? How can I decide?/Wives, the day of our death, are as fond as a bride.” Both airs are set to traditional English ballad tunes. It seems likely that Hogarth saw in this vernacular riposte to continental musical traditions a parallel with his own uniquely English depictions of modern life in London.

The painting is set in an ambiguous space, part prison and part stage, which situates the interplay of reality and fiction suggested in the Latin motto inscribed on the banner over the stage: “Veluti in speculum” (as in a mirror). The figures seated in boxes at the sides of the stage, occupying what were considered to be the best seats in the house, are recognizable portraits. Of particular note are John Gay, the shadowy figure at the foot of the staircase, and John Rich, standing immediately in front of Gay. In the foreground, Lavinia Fenton, the actress playing Polly Peachum, meets the gaze of the enthralled Lord Bolton; at the end of the season he would install her as his mistress and they would remain together until his death in 1754.

YALE CENTER FOR BRITISH ART, PAUL MELLON COLLECTION